This year is going to be decisive in many crucial aspects of everyday life – 2024 is being hailed as the most biggest election year in history, with half of the world participating in regional, legislative, and presidential elections. Geopolitical tensions were already among the biggest causes of market swings for investors, as we entered the new year, and many of the upcoming results will determine how those pressures will be exacerbated or resolved. There is also growing distrust among public in the integrity of elections themselves, together with the potential for spreading misinformation online and algorithm manipulation during the electoral campaigns. In certain countries, there is also a high risk of manipulated results and mass protests in response to them.

Asia first.

In only 10 days, Taiwan will hold a significant presidential election. US policymakers will closely monitor the results for insights into relations with China, which reiterated its commitment to “reunification” with the self-governing island during Xi Jinping’s year-end address. After which, Indians are set to vote in April and May. The country is rapidly emerging as a global manufacturing powerhouse, attracting bullish sentiments from investors.

Next, comes the Europe. European Russia, the most populous part of the country, has been in war with Ukraine for the past two years. This has impacted everything from energy to commodities. Both sides, however, show no signs of achieving victory or willingness to compromise. Russians will head to the polls on March 17, while Ukraine’s planned presidential vote on March 31 might be postponed due to martial law. The European Parliament election in June is expected to bring disruption to establishment parties, and the UK economy is under scrutiny as Rishi Sunak promises a general election in 2024.

Lastly, the Americas. The US presidential election cycle kicks off this month. The campaign season, covering topics such as the economy, immigration, infrastructure, and foreign policy, will receive ample airtime. The November 5 vote will not only determine the next US president, but also include Senate and House races, along with gubernatorial elections. South of the border, Mexico will hold a presidential vote in June, that could impact cooperation on trade and border security with its northern neighbour. Meanwhile, Venezuela heads to the polls in December, with a predictable outcome as the country gears up for a showdown with energy-rich Guyana.

In a distorting mirror…

With all that happening around the world which can have dire consequences, it’s hard not to feel anxious. Unless you’ve been avoiding news over the last year, you’ve seen how much progress has been made in artificial intelligence, and the way information shared online, is not always to be trusted.

Truth has long been a casualty of war and political campaigns, but now there is a new, stronger and more accessible weapon in the political disinformation arsenal – generative AI, that can in an instant clone a candidate’s voice, create a fake ‘interview’, or churn out bogus narratives to undermine the opposition’s messaging. This has already been happening in the US.

Now, voters can never be certain that what they see and hear in the campaign is real.

A political advert released by the Republican National Committee portrays a dystopian scenario should President Joe Biden be re-elected: Explosions in Taipei as China invades, waves of migrants causing panic in the US, and martial law imposed in San Francisco.

In the meantime, it’s forecasted that 100,000 hackers from China will target voters in Taiwan’s upcoming general election.

In another surprising video, Hillary Clinton appears to endorse a Republican, expressing her admiration for Ron DeSantis: “I actually like Ron DeSantis a lot. He’s just the sort of guy this country needs.”

Both videos are deepfakes, images generated by artificial intelligence.

It is hard to measure how effective these tactics are, but as we’re entering the era of hyper-personalisation, adding AI will allow the creation of unlimited numbers of distinct messages, each hitting the most sensitive strings. Swing voters, who usually make their minds up in the final days of the campaign, are a great target. Campaigns organisers can now access detailed personal data about them; from what they read to which TV shows they watch, to determine the issues they care about, and then send them finely calibrated messages that might make win their vote.

At the same time, it’s never been easier to create deepfakes and so members with harmful intentions could start introducing the type of information they want people to see via seemingly harmless links. As they gain control over the content people consume, they may mass create personalised messages to convey more pointed political messages. This could include urging voters to participate in protest marches on contentious issues like gun violence or race. And it doesn’t stop there. Those behind harmful campaigns can employ various strategies until they identify an approach that proves effective.

And I don’t know if you feel the same, but I feel like our societies are being more and more polarised, and only the extreme views can be heard and seen. Yet, polarised societies are less resilient to external threats and their elites are more inbred and preoccupied with their own tensions, which of course distances them from dealing with reality.

A country where kids learn in schools how to differentiate truth from fake news.

Up until now, people with mischievous intent have been restricted by their lack of expertise or access to sophisticated tools. You could quickly spot a fake. Generative AI, which produces text, images, and video by emulating patterns from existing media, is democratising disinformation by making it accessible, inexpensive, and more persuasive. What’s worrying is that, when the capabilities of a large number of people with harmful intentions are enhanced through partial automation, then that creates a new threat model.

Such constant barrage of divisive propaganda has instilled a sense of vigilance in Taiwanese society. Schools actively incorporate media literacy and critical thinking into their curriculum, and citizens, along with ‘civic hackers,’ are encouraged to report any suspicious content.

Fact-checkers are finding find it harder to detect AI messages where the use of language is closer to the way people talk in Taiwan. Some Taiwanese influencers are also being paid by Beijing to reinforce its propaganda.

Watermarking doesn’t work.

In an ideal life, we should see equal efforts and successes in developing AI tools counteracting and able to determine whether a certain content is truthful or has been distorted. Yet, researchers tested AI watermarks that has been created to attempt this —and broke all of them.

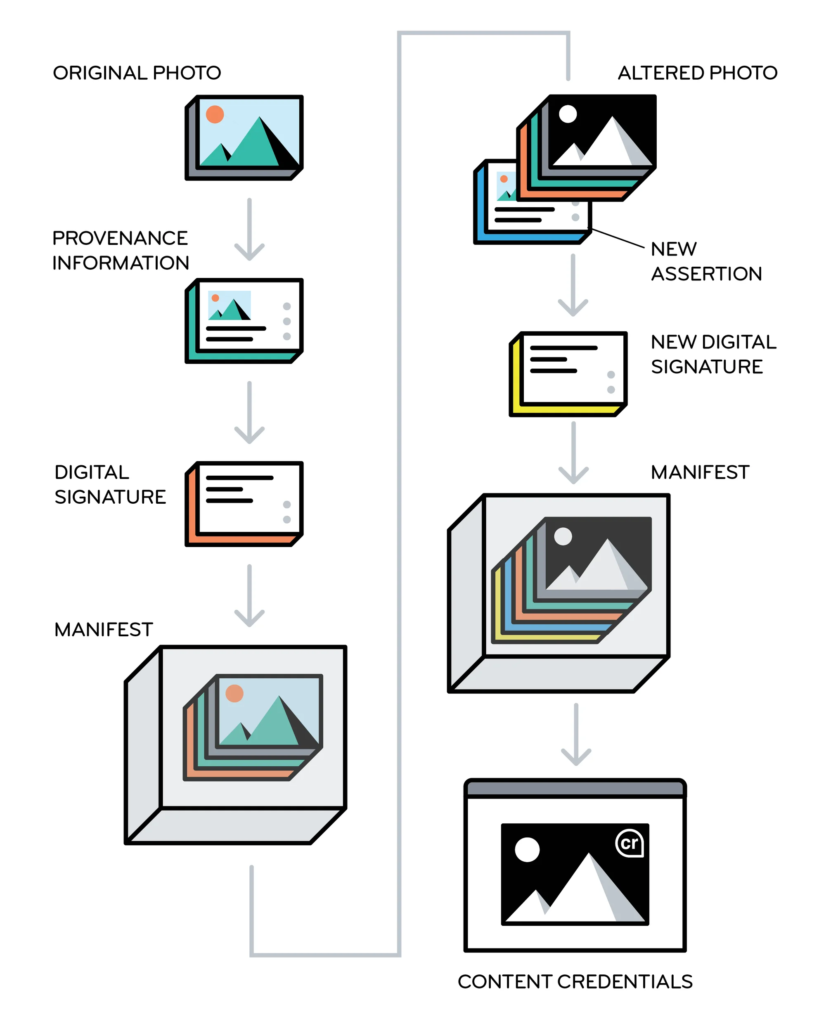

There are a couple of good ideas on how to validate information. For example, a couple of big media organisations are making a push to use the C2PA’s content credentials system to allow Internet users to check the manifests that accompany validated images and videos. Images that have been authenticated by the C2PA system include a little “cr” icon in the corner. Users can click on it to see whatever information is available for that image—how and when the image was created, who first published it, what tools they used to alter it, how it was altered, and so on. Its biggest drawback so far is that viewers will see that information only if they’re using a social-media platform or application that can read and display content-credential data.

Towards human-centred AI

It is easy to blame AI for the world’s wrongs (or for lost elections), but there’s a twist: the underlying technology is not inherently harmful in itself. The same algorithmic tools used to spread misinformation and confusion can be repurposed to support democracy and increase civic engagement. After all, human-centred AI in politics needs to work for the people with solutions, that serve the electorate, not the chosen few.

There are many examples of how AI can enhance election campaigns in ethical ways. For example, we can now program political bots to step in when people share articles that contain known misinformation. We are already seeing the seeds of it on popular social platforms like X and Facebook. We can deploy hyper-targeted campaigns that help to educate voters on a variety of political issues and highlight the topics most important to them, and enable them to make up their own minds. And most importantly, we can use AI to listen more carefully to more diverse population including those disadvantaged ones, and make sure their voices are being clearly heard by their elected representatives.

A potential approach to curbing deepfake propaganda involves tightened regulation. Enforcing more stringent guidelines on data protection and algorithmic accountability may help mitigate some of the misuse of machine learning in politics. However, regulations usually lag behind technological advancements.

When regulators finally start discussing the legal frameworks for AI in politics like AI Safety Summit and the UK and December’s AI Act in EU, I do hope voters will use common sense and put extra effort to verify and cross-check information, in order to select those representatives that will have public’s best intentions in mind. Not those, who know how to manipulate public view to their own benefit.